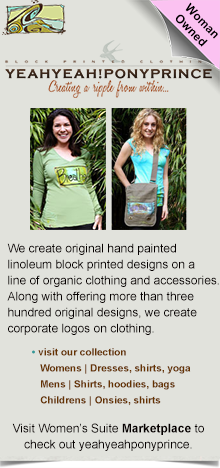

Changes over time of the actual Grammy statuettes:

John Billings operates a small manufacturing studio just outside Ridgway, Colo., where the Grammy Awards statuettes are made each year.

“When we’re making Grammys, we don’t know whose Grammy that’s going to be, so we don’t have one favorite,” Mr. Billings said, adding: “They’re all just like children. I really never try to question why someone is getting an award; I do sometimes question why someone is not.”

Before artists can hoist the five-pound award onstage in front of their peers, a lot of work must be done, which starts when the nomination list comes in. Mr. Billings and his team review it and estimate the number of Grammys that need to be cast to cover the nominees receiving the awards. In his 2,000-square-foot Ridgway, Colo., studio, the whirring of a polishing wheel and tapping of a hammer provide the soundtrack for his team of three, who tinker five days a week, year-round.

The awards are made of a custom metal alloy called grammium (yes, really), and are cast from three molds: one for the base, one for the gramophone cabinet and one for the tone arm, which holds the bell. After the pieces are cast, they go through a series of filing, sanding and polishing processes, and the gramophone cabinet and tone arm are plated in 24-karat gold.

Once dry, the three pieces are assembled, and each award is laser-etched with a unique serial number for authenticity. The Grammys used during the television broadcast are for show; Mr. Billings and his team engrave the names of winners onto plates after the event.

Mr. Billings’s relationship with the award began when he was 12, upon seeing his friend’s father, Bob Graves, make the first one in his garage. In 1976 Mr. Billings became Mr. Graves’s apprentice; he took over production in 1983 after his mentor’s death.

Over time the trophy, like the Grammy Awards show itself, has evolved. Since the first ceremony, in 1959, five different designs have been created; the last major face-lift came in the early 1990s, when Mr. Billings said he spent a year sketching and a few months fashioning three prototypes from scrap metal in his studio. The goal was simple: to keep the gramophone and its Art Deco influences but rework the tone arm, which was prone to breaking because of its thinness.

Nearly 30 years later, Mr. Billings said he remains content with his design.

“I think it’s going to stay exactly where it is,” he said of the current Grammy. “I don’t see a reason to change it. It’s become very iconic. People recognize it and understand what it symbolizes.”

Once Mr. Billings and his team have made the finishing touches on each set of Grammys, it’s time to send them to Los Angeles — but not via FedEx or U.P.S.

“I’ve always just hand-delivered them,” he said. “I just think it would be a nightmare to try and ship these. In the old days, there weren’t so many Grammys, so I would put them in my truck and make several trips.”

These days, Mr. Billings attaches a cargo trailer to his truck for the 2,000-mile round-trip journey. When the last Grammy is packed away and the trailer is locked, the team takes a moment to pause.

“We open a bottle of champagne and write a date on the bottle and how many Grammys were made for that year,” he said. “That caps it off — the Grammys are done, now they’re on their way. Then we start making them all over again.”